Historic California Coastal Ranching Landscape

Agricultural Legacy of Rancho Tajiguas

The Gaviota Coast is one of the last remaining examples of an historic California coastal ranching landscape, representing a cultural and scenic landscape and a way of life that is becoming increasingly rare. Rancho Tajiguas is perhaps the most intact example of a historic Gaviota Coast ranch, eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places for its ability to convey its historical connection with ranching and agriculture on the Gaviota Coast for a period of more than 200 years. Importantly, Rancho Tajiguas has maintained continuous ranching and farming operations since at least the late 1790s, perhaps the longest documented in Santa Barbara County[i].

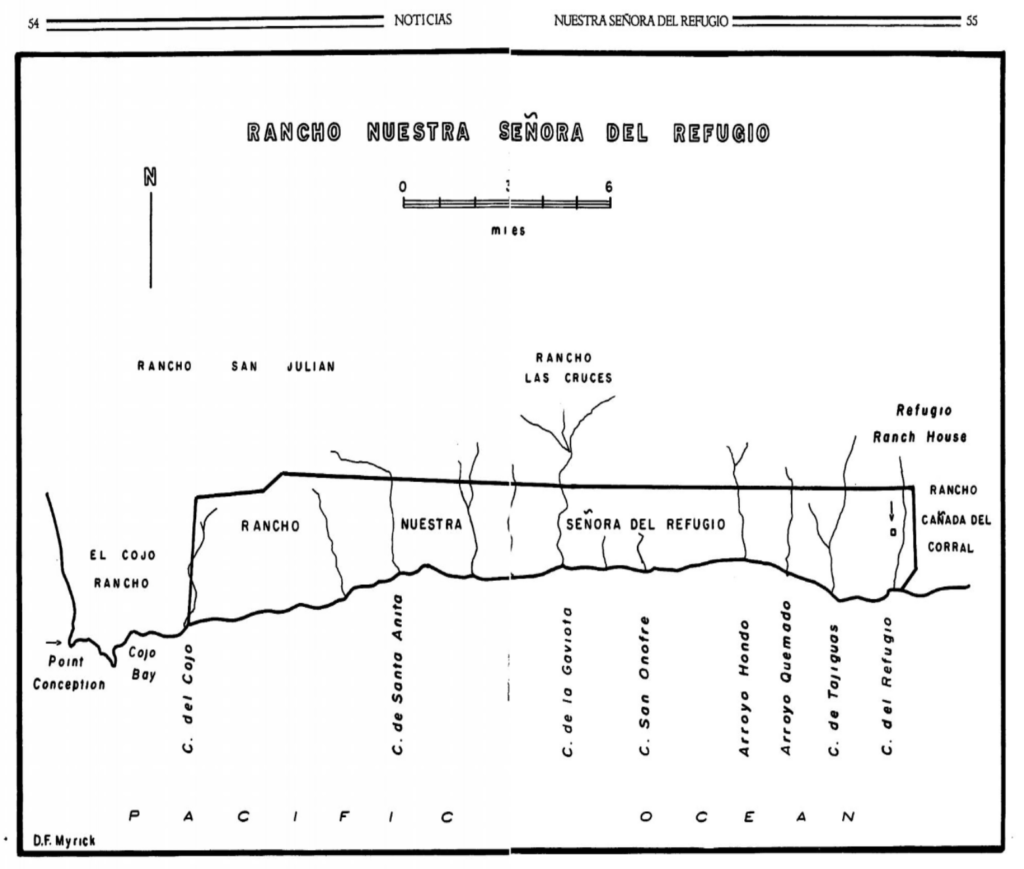

Circa-1793, when California was under Spanish rule, a land concession encompassing grazing rights but not land ownership was granted by the colonial government to Jose Francisco de Ortega. Known as “El Capitan” for which El Capitan State Park is named, Ortega was a sergeant for the Portola Expedition that explored the Gaviota coast in 1769 and had a formative role in Gaviota Coast history. Ortega’s concession, called Rancho Nuestra Señora del Refugio, was the only land concession licensed under Spanish rule in what today is Santa Barbara County. Rancho Nuestra Señora del Refugio extended from Refugio Canyon west to Tajiguas Canyon, terminating at El Cojo Rancho (now The Nature Conservancy’s Dangermond Preserve)

After Jose Francisco Ortega’s death, his concession was managed by his sons, Jose Maria Ortega, and Jose Vincente Ortega. Jose Maria Ortega likely resided in Tajiguas Canyon where a house had been built by circa-1800.[i] The Ortega family’s concession was among the most successful in colonial-era California, and included stock-raising, 3,000 grape vines, 400 fruit-bearing trees and wheat fields irrigated by aqueduct and possessing a grist mill for grinding grain. According to a least one source, the first lemon grove in California was planted at Rancho Tajiguas in 1802. Much of the work cultivating crops and running cattle was likely done by the forced labor of the Chumash.

“In Tajiguas there are also sowing grounds, which with the vineyards, which are their situated, are irrigated by the brook which constantly flows through the same…..The Cañadas of Quemada, San Onefre, La Gabiota, Santa Anita, and that of the Cojo are the places in which stock are kept during the winter seasons, because in those cañadas, there is no permanent water near the coast…. There also pertains to said inheritance two orchards situated in the principal cañada (Refugio), and another in that of Tajiguas in which there are vineyards, olive and other fruit trees.”

Description of Tajiguas Canyon by Antonio Maria Ortega in a 1827 letter to the governor as part of his family’s efforts to gain title to Rancho Nuestra Señora del Refugio, as translated.[v]

From 1821 to 1848, California was a Mexican territory ruled by a governor appointed by the central government. In 1834, Rancho Nuestra Señora de Refugio concession was granted to Antonio Francisco Ortega, becoming one of the first grants in the Santa Barbara region. (Cowen 1956: 67).

After California became a state in 1850, the Ortega family remained prosperous in part due to the demand for beef created by the Gold Rush and the subsequent influx of settlers into California. However, a devastating drought between 1862 and 1864 combined with a downturn in the cattle trade drove many Hispanic landowners into bankruptcy and Santa Barbara County’s cattle herds declined from around 300,000 head before the drought to about 5,000 in 1864[vi]. The Ortegas lost nearly all the lands once constituting Rancho Nuestra Señora de Refugio through a series of sales and actions, ending with the sale of El Rancho de Tajiguas on January 7, 1870, by sheriff’s auction, for $2,700.00 to Amasa Lincoln and Frank Young.[vii] By the early 1890s, following an influx of non-Hispanic settlers and discrimination by newly-arrived Anglos against Hispanics, many Hispanic families like the Ortegas that had owned large ranchos, had been reduced to the status of tenants and ranch hands.[viii]

After acquiring Rancho Tajiguas in 1870, Amasa Lincoln and Frank Young ran about a thousand head of sheep and a smaller herd of dairy cattle on the property. In 1884, the Youngs sold the ranch to Lawrence More. A friend of More described Rancho Tajiguas shortly after he acquired the property:

“Its arroyo or creek never fails to reach the sea, and for all purposes…is the best between Hueneme and Gaviota…Tajiguas rancho is a portion of the grant Nuestra Senora del Refugio and contains 2,340 acres of land of which 500 are arable, and 200 can be irrigated… Fine cattle and horses were feeding near the creek. Beyond, a thousand sheep, watched over by a faithful Basque, were grazing on the slope of the western ridge. A mile from sea our path was crossed by a stream of clear, cool water, flowing from a never-failing spring….Passing between an olive orchard and the old vineyard (which once afforded wine for the good Padres of the Santa Ynez Mission, but now yields its rich juices to a myriad of wild bees) we arrived at our destination… I found a great number of brood mares with promising colts and mules that would delight the fancier to behold. For the present and until further immigration to this coast, and cheaper labor Tajiguas must be devoted to stock raising…. In a sunny little cul-de-sac of an acre is his orchard of 80 lemon trees which this year have borne 25,000 lemons.”

Lemon groves planted in the early to mid-19th century were still in production, and in 1886, Lawrence More exhibited Sicilian lemons from Rancho Tajiguas at the Santa Barbara Citrus Fair (“The Citrus Fair, Santa Barbara’s Annual Exhibition of Fruits and Flowers,” Morning Press, February 25, 1886).[i] Olive trees surviving on the ranch from the Spanish and Mexican eras were also present as noted in a 1904 newspaper article by Elwood Cooper (“The Olive in California,” Pacific Rural Press, June 4, 1904).

By the early 1920s, the Mores were still cultivating lemons, added walnuts, and also leased land to lima bean farmers. According to an early 20th century newspaper article, Rancho Tajiguas was the northern-most limit of profitable lima bean cultivation in California (“Where They Know Beans,” Morning Press, May 9, 1908).)

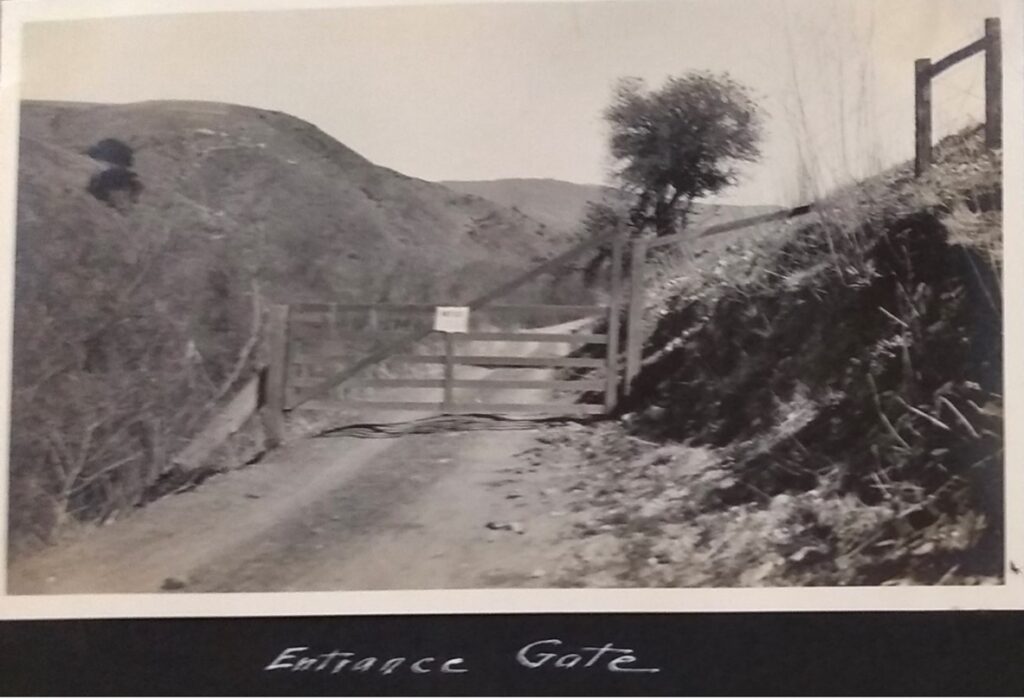

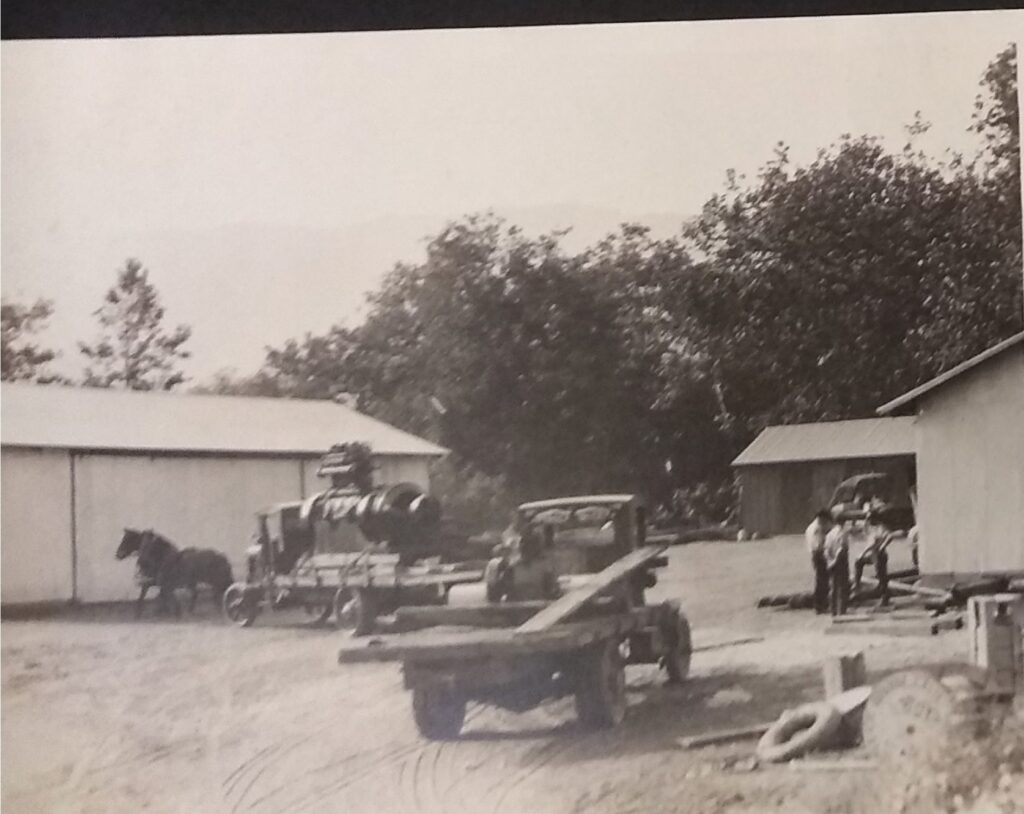

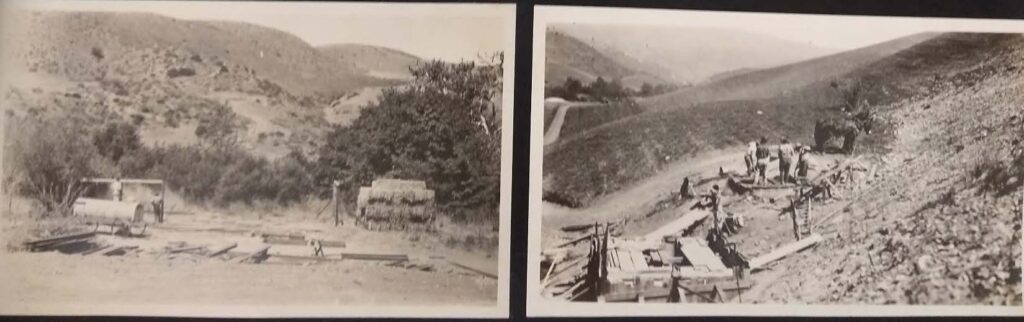

Kirk B. Johnson purchased Rancho Tajiguas from M. Rose More and her brother Clifford for $200,000 in 1923, intending to transform it into “a Model Ranch”. (“Tajiguas Sold for $200,000 to K. Johnson,” 1923 Morning Press Article).[iv] Ranch infrastructure added shortly after Johnson’s acquisition of the property included two reservoirs, 13 wells, and an extensive irrigation system, among other improvements, documented by photographs and detailed topographic maps prepared between 1924 and the mid-1930s.

Kirk Johnson, Tajiguas Scrapbook, Santa Barbara Historical Museum, Gledhill Library

Kirk Johnson, Tajiguas Scrapbook, Santa Barbara Historical Museum, Gledhill Library

Kirk Johnson, Tajiguas Scrapbook, Santa Barbara Historical Museum, Gledhill Library

Kirk Johnson, Tajiguas Scrapbook, Santa Barbara Historical Museum, Gledhill Library

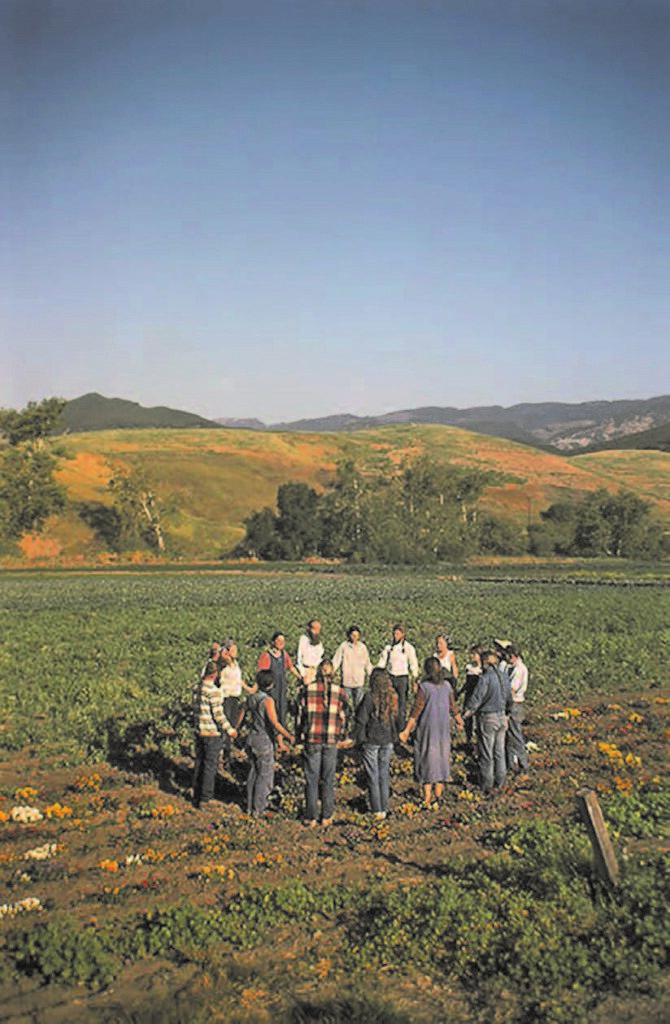

After the Johnsons sold Rancho Tajiguas in 1954, the property changed hands several times without substantial changes to the agricultural operations. In 1976, Rancho Tajiguas was purchased by the Brotherhood of the Sun, also known as Sunburst Farms, a commune founded in the 1960s by Norman Paulsen. Sunburst raised a wide variety of agricultural products at Rancho Tajiguas, which at the time was said to be the largest organic farm in the United States. In addition to growing fruit trees, vegetables, wheat, nuts, and other crops, members raised naturally fed, hormone-free goats, sheep, cows, and chickens. By 1981, faced with financial trouble and several lawsuits, Sunburst sold Rancho Tajiguas.